Our Fundamental Challenge

After 15 years of working on the frontlines of the movement to end homelessness, I have gradually come to believe that our sector's biggest challenge is something we almost never talk about, yet when I describe it to colleagues, there is near universal agreement about its role and impact.

Our biggest issue is NOT:

- NIMBYs

- BANANAs (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone)

- The Trump Administration

- The Cicero Institute

- Sensationalized content on social media

- Frustrated community members

- Funding (and the perceived lack thereof)

- A lack of heart and good intentions

- A lack of great ideas and innovation

- A lack of smart, talented and dedicated people

Instead, to quote the great systems theorist Donella Meadows:

- The destruction [systems] cause is often blamed on particular actors or events, although it is actually a consequence of system structure. Blaming, disciplining, firing, twisting policy levers harder, hoping for a more favorable sequence of driving events, tinkering at the margins – these standard responses will not fix structural problems.

So, what is the deep structural issue that continues to trip us up at every turn?

Decentralization.

Since the dawn of The Modern Homelessness Crisis in the early 1980s, we - the homeless service sector - have fundamentally decentralized our response, leaving every state, county, Continuum of Care, city, and service provider to their own devices to figure out what to do. This fragmentation drives at least six extremely powerful feedback loops that are making it exponentially harder to solve this crisis.

This is the longest article I will ever post, but it is my best attempt to succinctly capture all of these dynamics in one place.

#1 - Local Government Infighting

I have spent the majority of my career either working directly in or advising local government agencies.

I probably shouldn't say this, but to be completely honest, a significant portion of my time in these roles always comes back to the same issue - helping a given jurisdiction navigate its working relationship with neighboring communities and other governmental entities (e.g., city vs. city, city vs. county)

Why are these conflicts so prevalent?

Because of insufficiently coordinated and enforced state and federal strategies for ending homelessness, the thousands of city, town, and county governments across our country are each independently responsible for addressing homelessness in their own local way.

To dramatically oversimplify, every government agency essentially has two options:

- Option A - Attempt to house and provide services for everyone who is homeless

- Option B - Do not provide housing and services and instead redirect people to other communities or agencies

There are two big reasons why local leaders do not pursue Option A:

- The cost of providing housing and services is substantial (especially without sufficient state and federal support).

- There is a pervasive and pernicious belief that most people experiencing homelessness are not "local" (i.e., they became homeless somewhere else and then moved to the community). This belief signals an assumption that other communities have already selected Option B.

Even though data consistently shows the opposite to be true (e.g., 96% of people experiencing homelessness in California only access services in one Continuum of Care), the fear is real and must be overcome. And it is important to see that the hyper-localization of our response to homelessness makes this dynamic worse because it is not easy for civic leaders to see what is happening outside of their particular jurisdiction and coordinate.

This all drives our first feedback loop:

- Many communities blame local homelessness on [insert neighboring city / county].

- This perspective creates a reluctance to invest local resources.

- This lack of resources results in increases in local homelessness.

- This increase in homelessness fuels feelings of otherness, perpetuating the cycle.

The Feedback Loop ...

The Kind of Headline It Explains ...

The Kind of Headline It Explains ...

#2 - "The Homeless Industrial Complex"

Over time, the term “[insert industry] industrial complex” has come to connote nefarious and self-serving tendencies within a given economic sector. It is:

- A socioeconomic concept wherein businesses become entwined in social or political systems or institutions, creating or bolstering a profit economy from these systems. Such a complex is said to pursue its own financial interests regardless of, and often at the expense of, the best interests of society and individuals.

To be very clear, in all of the time I have been working to end homelessness, collaborating with hundreds if not thousands of colleagues, I have not once met a person who is “pro-homelessness.” There is no grand, corrupt conspiracy to perpetuate homelessness for the enrichment of those working in this space. Every person I have met in this field is genuine in their desire to help people and make a difference. And frankly, social workers and care providers should be more highly compensated, given the stress, demands, and importance of this work.

Nonetheless, it is common to hear frustrated community members claim that the people working to solve homelessness are in fact part of "the homeless industrial complex.”

While this insinuation certainly stings, in all fairness, the social service sector as an “industry” is not above reproach.

No one wants homelessness, but over time, because society has failed to take the necessary steps to prevent it from happening in the first place, a large and robust homeless service system has emerged to try to help people regain housing.

Unfortunately, as anyone who has worked in this field will know all too well, structural inefficiencies often emerge as these social service systems grow, which makes solving homelessness even harder than it already is. The key is seeing that this is primarily driven by decentralization and a lack of meaningful coordination.

- “Silos” form when departments, organizations, or agencies operate independently without sharing information or coordinating activities.

- Without coordination and data sharing, it’s impossible to effectively measure what works and what does not.

- Without a process for determining what works and what doesn’t and investing accordingly, many communities get understandably frustrated and default to creating "new" programs and organizations, thus perpetuating and exacerbating the cycle (importantly, most of the time this so-called "innovation" is just rebranding or renaming existing programmatic interventions).

The Feedback Loop ...

The Kind of Headline It Explains ...

#3 - Chronic Homelessness

It is critically important to recognize that the fragmentation and unnecessary complexity in our social service systems impacts the most vulnerable the most profoundly.

When people experience homelessness for long periods of time, we often make them the subject of the problem.

- "It's a choice."

- "They're service resistant."

- "They're just too sick to help."

While there are of course people who can be very hard to engage, we must recognize the ways in which our siloed and decentralized systems make it harder for people to access the help they need.

- By definition, people experiencing chronic homelessness have disabling health conditions (physical health, mental illness, addiction, traumatic brain injuries).

- When our systems are confusing to navigate or have high barriers to access, people understandably disengage and become distrustful.

- As this happens, people's underlying challenges often worsen, which makes it even harder to help them later.

The Feedback Loop ... The Kind of Headline It Explains ...

The Kind of Headline It Explains ...

#4 - Loss of Institutional Knowledge

As our systems become more complex and fragmented, it becomes extremely difficult for any one person or organization to gain perspective on how all of the pieces actually fit together.

This is exacerbated by the fact that our movement does not have a shared story describing how we got here or a shared framework / strategy guiding our efforts moving forward.

Instead, individual human beings come into homeless systems of care with preconceived ideas and assumptions about what's driving homelessness and how we should be responding.

The result, as concisely and beautifully stated by Nithya Raman, Los Angeles City Councilmember and Chair of the City’s Housing and Homelessness Committee, is that:

- "We have 15 different Council Districts and 15 different approaches to homelessness."

Unfortunately, as leaders and practitioners do gain more knowledge and understanding, the inevitable - life itself - happens:

- People move on to other jobs or projects.

- They get burned out and quit.

- Some simply retire.

Because of the way we have decentralized our response, this leadership turnover means we are constantly losing hard earned institutional knowledge rather than absorbing it into our broader collective strategy and efforts.

As a former colleague who used to work for the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) once described it to me:

- We are never going to solve homelessness in Los Angeles because it's like the tide. Every few years a new group of leaders washes in with "new" insights and "new" ideas. However, after a few years, after they finally ascend the learning curve to understand what really works, they wash out, a whole new group comes in, and the process starts over again.

I now like to refer to this phenomenon as "the leadership tide."

The Feedback Loop ...

The Kind of Headline It Explains ...

#5 - Short-Termism

In an important way, the leadership tide actually helps to drive our first feedback loop - local government disinvestment.

Local leaders, particularly political leaders, who know they will only be working on this issue for a relatively short period of time before moving on to something else, are not inherently incentivized to make hard, long-term investments or policy decisions. Instead, the incentive structure is often oriented towards quick wins that address the symptoms of the problem.

Tragically, the resulting symptom-relieving activity often takes inhumane and counterproductive forms, such as pushing encampments from one neighborhood to the next or even criminalizing the condition of being without shelter or housing options.

Ultimately, of course, there is an opportunity cost to all of this. The time, energy, and resources that go into reactivity invariably fail to deliver lasting results, but by then, conditions are even worse, the public is even more frustrated, and the temptation is to double down.

The Feedback Loop ...

The Kind of Headlines It Explains ...

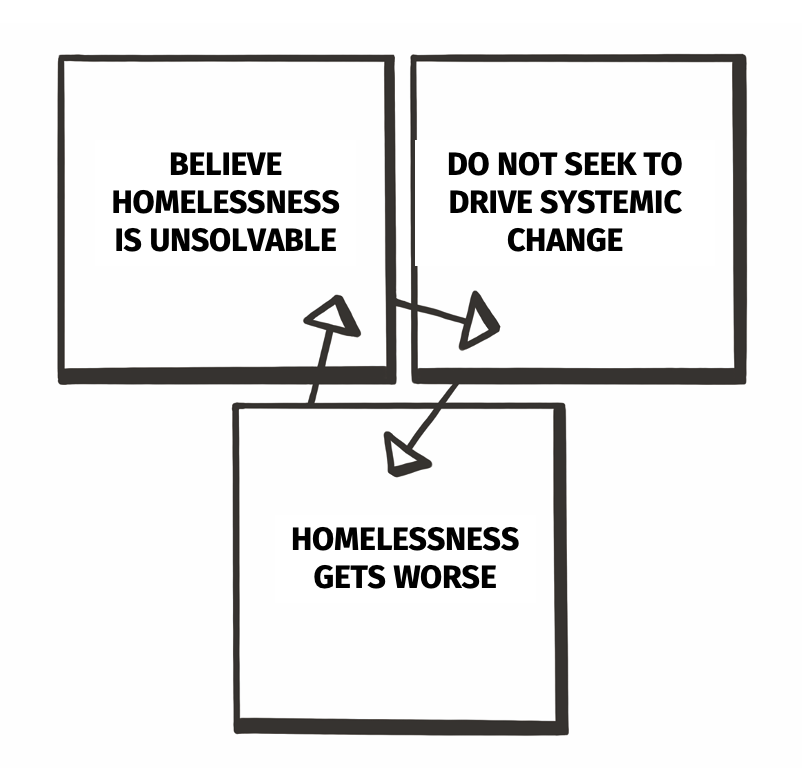

#6 - Cynicism and Hopelessness

Given all of these dynamics, it's easy to lose hope.

As San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown famously declared in the early 2000s:

"Homelessness in unsolvable."

Homelessness is not inevitable, as evidenced by the fact that it has emerged and then disappeared many different times throughout our nation's history.

However, the sad truth is, it increasingly feels unsolvable.

And that belief, that cynicism and loss of hope, keeps us stuck with an inhumane, incompassionate, and ineffective status quo that nobody wants.

The Most Harmful Feedback Loop of All ...